Trump, Venezuela, and the Return of 19th-Century Politcs

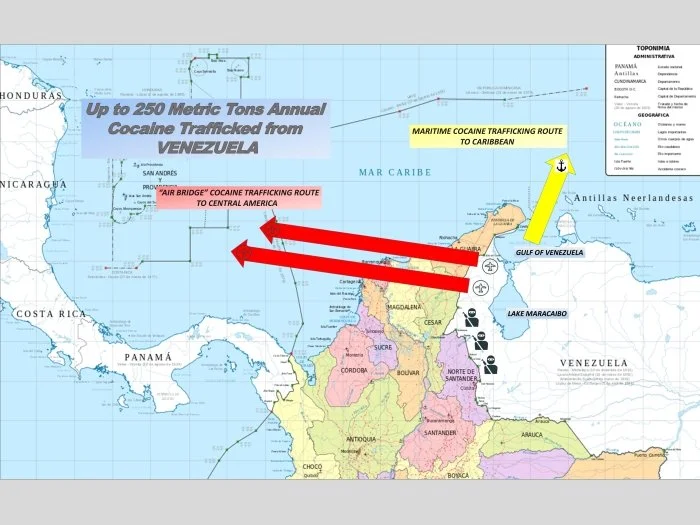

Early on Saturday morning, the United States attacked the Venezuelan capital of Caracas, launching a series of Airstrikes and capturing Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and his wife, Cilia Flores. According to Gen. Dan Caine, Trump’s Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, by approximately 4:30 Eastern Time, Maduro and Flores had been transferred to an American warship pending transport to the United States, where they face Narco-Terrorism and Cocaine Importation Conspiracy charges, according to a recently-unsealed Grand Jury indictment in the Southern District of New York. These charges come in addition to those filed in March 2020 during Trump’s first term, when began to allege that Venezuela played a role in the ongoing American drug crisis.

Justice Department, ©2020

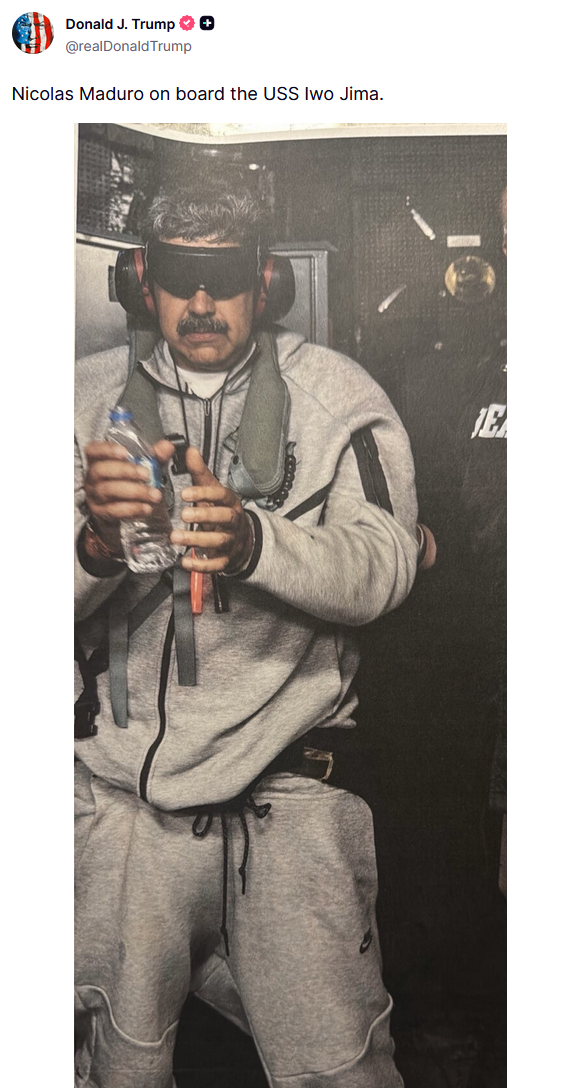

This attack, which killed at least 40 Venezuelans both military and civilian, occurred without any American casualties. The president both in a statement to the press and on his Truth Social account, treated it as a victory, a testament to his and the United States’ strength, posting videos of the airstrikes in Caracas and photos of Maduro in captivity on his official Truth Social account. The reactions to it have been decidedly mixed, however. There were public celebrations of Trump’s capture of Maduro by members of the Venezuelan diaspora in Santiago, Lima, Quito, and Miami. However, the attack also has been met with protests in the US and abroad, and censure from the editorial boards of major newspapers such as The New York Times. Additionally, this attack drew condemnation for its blatant violation of international law from the United Nations.

President Trump, however, did not acknowledge the possibility of criticism during a press conference on this attack, focusing instead on fitting it into a narrative of executive strength against the “drugs and gangs” that compose some of Trump’s regular political bogeymen, and drew equivalency between it and his controversial domestic troop deployments. Several elements in particular, though, gave this speech, and by extension, the American intervention in Venezuela, far broader implications for the course of international politics.

“Under Maduro, Venezuela hosted foreign adversaries and acquired dangerous weapons that threatened American lives… …Under our new national security strategy, American strength in the Western Hemisphere will never again be questioned. The future will be shaped by the protection of commerce, territory, and resources central to national security. These principles have always defined global power… …Every political and military figure in Venezuela must understand that what happened to Maduro can happen to them.”With these statements, Trump positions the airstrikes on Caracas and the capture of Maduro as a demarcation of an American “Sphere of Influence”. Maduro, who had long been a vocal opponent of the United States, cultivating an increasingly close relationship with China and Russia and seeking entry into the BRICS+ organization, is explicitly positioned as an exemplary warning to other leaders within the region.

Trump presents a version of spheres of influence stripped of any ideological justification beyond the claim of strength - might makes right. While American involvement in regime change in Latin America is not a political novelty (e.g., during the 20th century, the United States conducted a substantial number of regime change operations, most recently 1989’s Operation Just Cause), historically there has at least been a veneer of ideological justifications. But with this action and Trump’s stated reasoning - that nations within the American “Sphere of Influence” must subsume their agency over “commerce, territory, and resources central to national security” to United States’ interests based on geographical proximity and United States’ military superiority - the ideological varnish that “justified” those 20th century actions is stripped. Instead, it represents a further step in the ongoing international trend towards the return of an older, almost 19th century form of geopolitics, a multipolar great-power realism.

The idea that states with a certain level of power possess “spheres of influence"where they exert some level of leverage over the nations within is far from the most controversial idea within International Relations, particularly among realist thinkers. However, Trump presents here a version of spheres of influence stripped of any ideological justification beyond the ideology of strength. While he may post videos on Truth Social of cheering Venezuelan exiles in Florida, he makes barely a cursory attempt when speaking to the press to justify his actions as benefiting the people of Venezuela, stating that Maria Corina Machado, the noble peace prize-winning opposition leader, “lacks the support and respect [to govern Venezuala]” and US will “essentially administer the nation until that transition takes place” instead. More importantly, according to Trump’s speech, the United States will “will bring in our largest U.S. oil companies… …so the nation can generate real revenue again”.

This is a dark vision of international politics, on where “great powers” such as the United States, Russia, or China are entitled to subservience of weaker nations justified solely by their military and economic strength,and where the non-subseviance of a state within said sphere of influence is a casus belli. The emergence of this vision to the mainstream can be seen as early as 2014, when Foreign Affairs published John Mearsheimer's infamous essay “Why the Ukraine Crisis is the West’s Fault”, which justifies Putin’s actions in Crimea with the argument that Ukraine’s attempt to exit the Russian sphere of influence constituted enough of a provocation to justify a military response, a line of analysis Mearsheimer has further defended since the start of the full-scale Russian invasion in 2022. While less dramatic, that same logic of entitlement to sole agency within their sphere of influence can be found in China’s continued, militant, territorial claims in the South China Sea, in direct defiance of the 2016 Permanent Court of Arbitration ruling against said claims.

By justifying his actions in Venezuela in these terms, Trump creates a retroactive legitimacy for other “great powers” to justify their own actions as “defending their spheres of influence”, and sets a precedent of acceptance for similar acts of aggressive regime-change that has worrying implications for the militarily and/or economically weak neighbors of “great powers” globally. The implications of this are bluntly laid out by Yale’s Prof. Oona Hathaway in a phone interview given to The New Yorker’s Isaac Chotiner on the afternoon of the 3rd:

“Unfortunately, I don’t think there is a legal basis for what we’re seeing in Venezuela… …The dangerous thing here is the idea that a President can just decide that a leader is not legitimate and then invade the country and presumably put someone in power who is favored by the Administration… …And if the President can do that, what’s to stop a Russian leader from doing it, or a Chinese leader from doing it, or anyone with the power to do so? ”

Fundamentally, Donald Trump has tacitly endorsed a vision of conditional sovereignty, where weak nations are not protected by international law or norms and powerful nations are not bound by them. His actions and his foreign policy have pushed the United States closer and closer to becoming ideological, if not geopolitical, bedfellows with the very revisionist powers that were once considered America’s rivals.

It is too early to tell what will happen in Venezuela now. Trump has stated that the US will administer Venezuela transitionally, and that American Oil Companies will “revive” Venezuela’s Oil industry. However, at the time of writing this article, neither he, nor anyone in his administration, have offered anything resembling a concrete plan for how either of these would occur. Vice President Delcy Rodríguez, who has been sworn in as Venezuela's interim leader, has been defiant towards Trump on Venezuelan State TV, making clear that she and the rest of Maduro’s supporters within Venezuela's government still see him as the country’s legitimate leader. And Colectivos, the non-uniformed paramilitaries who Maduro’s government often deployed against opponents and protestors, have been gathering in Caracas in large numbers, though their exact reason for doing so is unclear. No matter the exact outcome within Venezuela, the Trump administration’s actions on the 3rd have already shifted the landscape of international politics, with the United States taking a further step away from the universalising ideals that defined (though were never fully realised by) the liberal hegemony it created, and towards a narrower, more realist international politics that condemns weak states to subsume their sovereignty to the self-intrest of powerful ones.

Image courtesy of AFP/Getty Images, ©2026. Some rights reserved.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the wider St Andrews Foreign Affairs Review team.