Locking Down the Protests

Photo by Hugo Morales and obtained courtesy of Wikimedia Commons under an Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

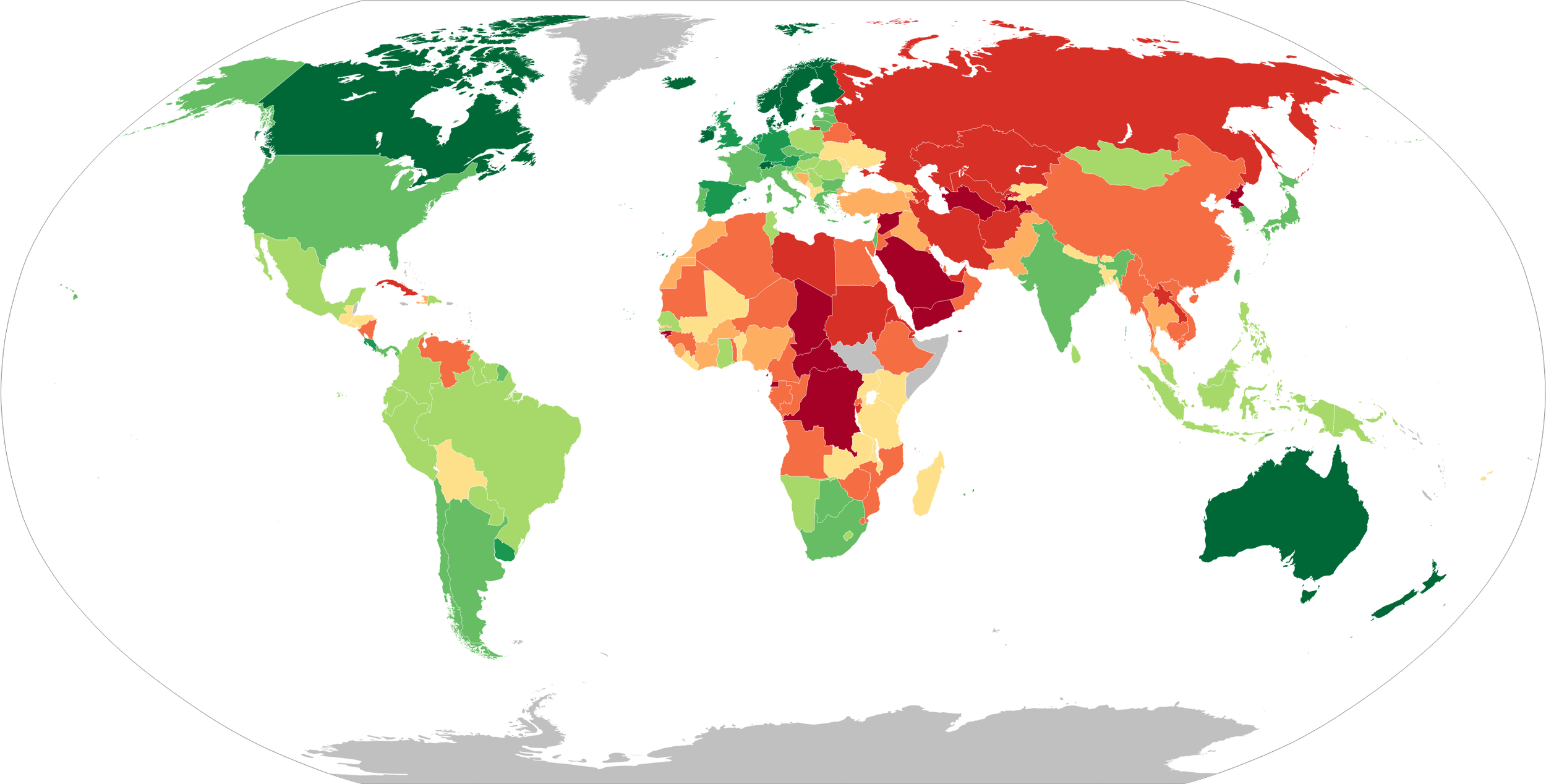

All other news seems somehow obsolete. It has now become impossible to scroll for news without being bombarded with depressing, and often contrary, coronavirus headlines. And rightly so. We are in the midst of a global pandemic, which is affecting much of the world and will continue to do so for months if not years to come. As of this, weekend almost 2.5 billion people worldwide are in lockdown, and that’s excluding the disease’s epicentre, China, which after months of complete isolation has finally managed to stabilise the numbers of infected people and consequently lifted its lockdown measures. The disease, which affected China first, then its neighbours and now largely the Western world has yet to fully take hold in Africa or South America. If it does, the consequences could be dire. Initially, in South America, the disease progressed along class lines. The early cases in Brazil, Uruguay and Ecuador all resulted from residents returning from Europe and spreading it through swanky parties. On the whole, though, they had the luxury of first-class private healthcare to fall back on. The same will not be the case if the virus becomes widespread in the coming weeks and months.

Chile finds itself second on the list of the most cases in South America (behind Brazil) but the number remains relatively low at 2,738, and the number of deaths has only just reached double figures. That notwithstanding, President Piñera had already called a state of catastrophe almost two weeks ago. Schools have been closed, gatherings restricted, and more stringent measures promised. How seriously the people have taken these measures is much harder to assess. Trust in the President is at all time low, with only 9% of Chileans believing their leader is doing an adequate job. Conversely, faith in local mayors and the National Doctor’s Association is at over 70%, indicating that the people will hopefully be responsible about the restrictions put in place. Already, the protestors who have been an unstoppable force over the last five months have moved their qualms indoors, sating themselves with a daily noise demonstration, using pots and pans.

Their protests began in October last year. On 6th October, Chileans took to the streets of Santiago, protesting against the 3% increase in the price of metro tickets. Less than a fortnight later that increase was reversed, but the revolution had been set in motion and the set of grievances stretched far and wide. The protests opened up wounds that had plagued Chilean society since Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship from 1973-1990. Despite record economic growth under Pinochet, increasing at twice the regional average over 15 years, and to an extent the governments that have succeeded him, inequality has remained high for a developed country and people have finally had enough. University students had called for the turnstiles to be jumped and multiple metro stations were vandalised and even set on fire. The movement has continued to grow in an irresistible fashion. The Chilean youth has shown that they are not afraid of the government and that they want change now. Even ambitious social reform proposals, including the introduction of a basic universal income, major changes to the unpopular pension scheme and raising the income tax for the wealthy have not sated the Chilean people. They want President Piñera’s head and they haven’t shown any sign of stopping until they have it.

Evidently, the coronavirus has, for now, put a stop to their progress, but these grievances won’t simply disappear. It is a movement run by students, both from high-schools and universities, mobilising for a total transformation of the society their parents, raging against the ‘machista’ institutions that run their country. Their protest hymn, ‘un violador en tu camino’ — ‘a rapist in your path’ — has become a global protest hit, accompanying marches from Delhi to New York. It reached its zenith on March 8th, international women’s day, with up to 2 million marchers flooding the streets of the capital to voice their discontent about issues of gender violence and institutional sexism. A global lockdown may well have taken some of the steam out of their sails, but the protest is surely far from over. Technology and social media will surely fan the flame in the intervening period, and when this is all over, and Piñera undoubtedly remains in charge, the protesters will return with a vengeance.